In each Sentry Story, we’ll describe an actual flight and share the view out the window and ForeFlight screenshots. You’ll see how Sentry can be used to make flying safer and easier, plus you’ll learn some tips for flying with datalink weather. Want to share your story? Email ipad@sportys.com

Learn more about the Sentry line of ADS-B Receivers:

Sentry Mini>>

Sentry>>

Sentry Plus>>

Sentry Story #6

Date: August 20, 2019

Aircraft: Robinson R44 helicopter

Route: 49IL to I69

Flight rules: VFR

Altitude: 2,000 MSL

Flying cross-country in a helicopter sounds exotic, but it’s really no different than doing it in a Cessna 172 or a Piper Cherokee. Sure, there are more potential landing sites, but the fundamentals of VFR flying remain the same: stay out of clouds and reduced visibility, and ideally find a smooth ride. Even the performance of a piston helicopter is similar to popular single engine airplanes (about 105 knots and 1000 feet AGL in the Robinson R44 I was flying).

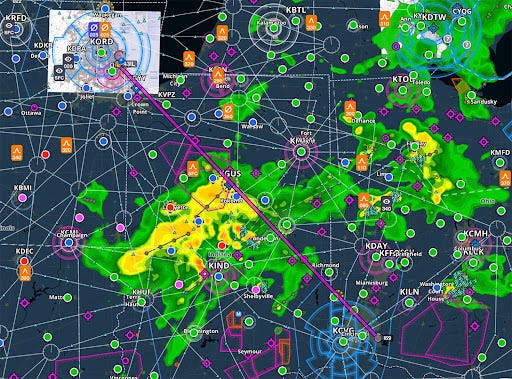

That was exactly the plan for this flight, where I was headed home after a wonderful weekend in Chicago with my wife. As usual, though, Mother Nature didn’t get the memo. When I opened up ForeFlight at the hotel, I saw a large area of rain and IFR conditions across my route of flight. Direct to destination was clearly not a good idea.

But like the cliche says, it’s best to skate to where the puck is going, not to where it is now. And the puck, or the rain in this case, was going northeast. It seemed like we could delay our departure just a bit and then fly around the back side of the weather, perhaps with a modest deviation to the south if conditions became marginal. One thing was for sure: in-flight weather from my Sentry would be essential for evaluating the changing conditions along this 2 hour and 30 minute flight.

With a good briefing and a solid backup plan in mind, we took our time preflighting the helicopter to buy some time and then lifted off from the very cool Chicago Vertiport. It’s the closest thing the Windy City has to Meigs Field these days.

After leaving the complicated airspace around Chicago, we headed south-southeast. I didn’t even try direct (although it would have worked for the first 50 miles), because I didn’t want to get tempted by a sucker hole. It can be hard to resist the temptation of a small gap at low altitude, so discipline is important in weather flying—as I like to say, “don’t look at the menu if you don’t want to order.” Once again, animated radar was a huge asset on this flight. Instead of just looking at green and yellow blobs, I watched how they were developing and where they were moving. This reinforced my plan to deviate to the south.

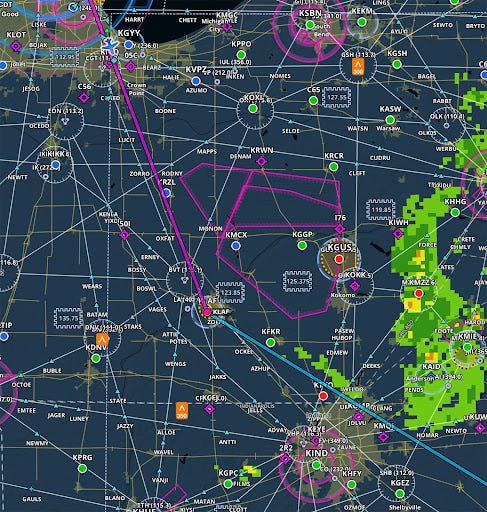

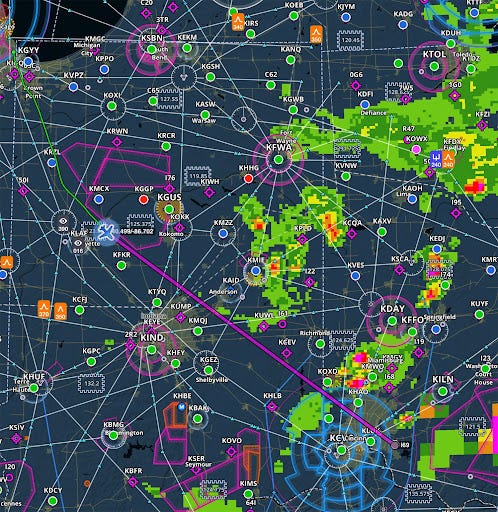

Around Lafayette, Indiana, it looked like we were getting on the back side of the weather, so I turned direct to I69. In making this decision, METARs were very helpful because avoiding the red cells on the radar image was not enough. The METAR map made it easy to keep a big picture view of ceilings and visibility: keep the green circles around me and avoid a lot of the blue and red off to the east!

This worked remarkably well, as it almost always does. There was a very thin layer of scud near Anderson, Indiana, but we kept it off the left easily. When you’re navigating around weather that is close by, there’s no substitute for your eyes. That was the key weather avoidance tool for this segment of the flight.

By the time we were within 50 miles of home, I thought my work might be done, but the unstable air mass around Cincinnati had one last twist. The southwestern tip of the weather started firing up into a storm, with yellow quickly becoming red and even purple in spots. That meant another deviation, and once again I wanted to stay on the back side of this developing system. This would require coordination with Cincinnati Approach and Tower, but they were gracious and helped me stay well clear of both the thunderstorms and the airline arrivals at CVG. It was another reminder that you must remain pilot in command at all times; don’t let perceived ATC pressure lead you to an unsafe decision.

After one last zig and zag, I landed at I69 in mostly clear skies. My deviations had added maybe 15 minutes to the flight, a very small price to pay for a safe and comfortable trip. The recipe remains the same, whether I’m flying a turboprop in the flight levels or a helicopter at low altitude: get a good preflight briefing, have a backup plan in mind, use a reliable ADS-B receiver, and verify everything with your eyes. If you do that, you can not only stay safe, but complete more trips and have more fun.

Want to share your story? Email ipad@sportys.com for a chance to be featured in one of our Sentry Stories.

Learn more

Read every edition of Sentry Stories here

Sentry line of ADS-B Receivers: